from the book “Mastering Multicamera Techniques: From Preproduction to Editing and Deliverables”

by

Mitch Jacobson

Category-5 Studios, New York

From a two-camera interview to a 26-camera concert special, multicamera production is being used more now than ever before. And with so many camera types, codecs and editing workflows for filmmakers to chose from, it’s hard not to suffer from Multicamera Madness! After being diagnosed recently with “multicamera-personality disorder,” I decided to write a text book and reach out in workshops to others who share the passion and desire to master multicamera production and editing.

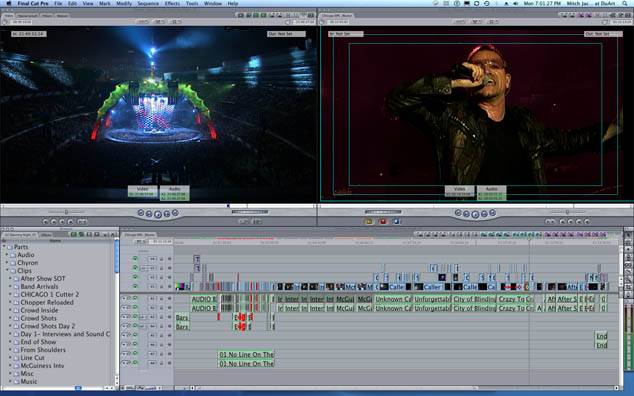

EDITING ELECTRONIC PRESS KITS ON-SET: YOUR FIRST CUT IS YOUR LAST CUT

On-set cutting for concert tour kickoff events is some of the most exciting editing I’ve ever done. I’ve worked with bands including The Rolling Stones, Aerosmith, Paul McCartney, and U2, and the basics are the same. We create EPKs (electronic press kits) that combine cut pieces like story packages, interviews with the band, b-roll, three or four songs that are multi-camera edited pieces ”“ and it’s super-fast turnaround, usually same day. You don’t have any time for errors. You have to be completely organized, the same way you would if you were shooting and editing any feature package in one day. By the time you ingest, prep and edit your first cut, it’s your last cut because of the same-day-satellite feed constantly looming in your deliverable’s future.

Setting up gear on location is a big deal. You have to have everything you need, because you can’t rely on an edit suite down the hall, or somebody else jumping in to help out if something goes wrong. You have to have all your tools — not just your editing equipment, but also software for graphics and sound. Then clients are going to throw things at you like Word files or PDFs or TIFs or files with notes about things that have to be re-conformed, so you really have to have your ducks in a row. I keep a full Adobe Production Premium Package, Microsoft Office and a tool kit of various applications on the road.

The US kickoff event for the U2 360º Tour presented some technological challenges that showed how preproduction really comes into play.

Even though they tour in the United States, their entire rig is based on European power — all of their gear runs at a whopping 220 volts at 50 cycles, twice the voltage of American power systems. In addition to that, they’re doing everything in PAL, and we’re NTSC. To do something as simple as adding a deck to record a line cut means converting the power AND the signal. In addition, we were doing an HD package, but the band was actually set up for SD, 16×9 anamorphic. So, we had to convert the power, we had to convert the format, and then we had to bump it to HD, just to get a line cut for editing—and have the full package done within hours of the concert!

On this particular U2 project, we shot with 5 Varicams (recording to tape) and combined them with the band’s cameras — U2 travels with 12 cameras with robotics, cranes and dollies, the whole deal. We wound up with a massive amount of footage to organize, catalog, convert and have ready so that everybody could get what they needed immediately.

Tape is a slower format for logging and loading than using a tapeless format like P2. A really fast P2 workflow uses MXF4Mac and ingests to Final Cut Pro without having to rewrap or transcode to QT. AJA KiPro is also cool for going directly to Apple ProRes and Telestream has the Pipeline system that I also use for quick turnaround and ingest-while-editing.

It really is frantic to try to get all this done in the middle of a concert. You can hear the band playing out there, everything is thumping, people are screaming, and everybody has their idea of what to put in the cut ”“ “Try this, let’s do that, let’s do this, let’s do that” — it really is nuts. A friend of mine once said, “It’s like jumping off of cliff and building your wings on the way down.”

THE ADVENT OF THE MODERN ELECTRONIC PRESS KIT

Back in the 70s, there was a little band called Journey. You may have heard of them.

They actually developed the system that we know as IMAG, Image Magnification for concerts. They started a company called Nocturne which is still around today– the largest touring IMAG company in the world. Basicly, they put up big screens at their shows so that people in the back row could experience the concert the same as if they were on the front row. It’s all about the close-ups, showing the tight shots of the hands and the head, the singers. That led to having full multi-camera production teams on tour with the bands.

And then along the line, the record companies discovered the need for electronic publicity including all these elements like B-roll, interviews and the music from the shows. They began to hire dedicated production companies to handle that, which is where Mark Haefeli Productions came in. All the legacy-type concert jobs I’ve done were produced and directed by Mark Haefeli, including the U2 360º Tour. Mark is a television pioneer who helped to develop the modern EPK by combining ENG crews with the touring IMAG productions.

A number of years ago, Mark and his team were asked to shoot performance footage for the Rolling Stones, capturing their stadium concert experience for news organizations and promotional purposes: everything from selling tickets to creating commercials. While Mark knew there were already cameras in place at these shows, he realized there was a problem with the setup.

“Back then, says Haefeli, it was just cameras out there shooting the action as it happened and going directly to the big screens. There weren’t even any recording devices to record the feed. They recorded the audio, but they never recorded the mixed master of all the cameras together, which we now know as the line cut.”

Mark began to record a line cut off the switcher, with occasional ISO decks as well. He also began to supplement that with additional multiple cameras that could divide and conquer to double-team a performance. For instance, 5 cameras shooting ENG style packages during the day could reconfigure at night to compliment angles shot with the band’s IMAG cameras to maximize coverage.

That’s because IMAG is looking for close-ups ”“ hands playing the instruments, individual band members, etc. — but for television, you also want group shots, reverse angles of the crowd, and big, global shots plus people getting off on the music. So, Haefeli’s cameras focus on that, and then, they would just combine that with the IMAG feeds into these EPKs — still the workflow that’s used today.

During the day, we take, say, five cameras, and they run around starting at 6 AM grabbing b-roll and interviews, so they shotgun out to the world and around the stadium or the event. After they’re done with the shots for the day, they come back, regroup, and become performance cameras for the actual concert.

Mark Haefeli: “Essentially, we walk out of there with a complete show under our belts. With remixed audio tracks, as well; half an hour after the show was over we were able to go right into post and edit what ultimately looked and felt like a multi-million dollar concert production of tremendous size.”

|

ENTER THE MOVIOLA MONSTER Desi Arnaz and his director of photography Karl Freund, ASC were the first to shoot filmed multicamera television programs with the I Love Lucy show (1951). They pioneered the 3 camera studio system that sitcoms employ today. They invented the hanging light grid, crab dollies and added a live studio audience. Their editor Dann Cahn, A.C.E. wrote the bible for multicamera film editing, and was the first to cut multicam– using the Moviola Monster, a four-headed Moviola for multiple film cameras and double system sound. "When I had signed up for the I Love Lucy job and arrived in my cutting room, two guys came in wheeling this new edit thing and I said to my assistant, What are we going to do with this monster? It won’t even fit in the cutting room. So we put it in the prop room and used it there. It was a Moviola with four heads––three for picture and one for sound. Its new name—The Monster—stuck." – Dann Cahn, A.C.E. It was retired more than 30 years later on "Designing Women" in the late ’80s, long enough for Dann’s son, Daniel Cahn, A.C.E., to grow up and also edit on the Monster. Now of course we have the luxury of non-linear digital editing systems but as much as things have changed, things have stayed the same. We still use the same studio systems and editing workflows that Desi and his team perfected in the 50’s. They are simply more refined and offer more options. [Ed. note: photo used for this article’s title graphic: Moviola Monster used to edit the first multicamera filmed program: "I Love Lucy Show" (1951) Courtesy Dann Cahn, A.C.E.] |

|

“WE LIVE AND DIE BY TIMECODE.” ”“ Ray Volkema, Editor, HDNet

Time code is the essential, original metadata, and a lot of the time, people get it wrong. Our work in multicam is designed around getting it right. A couple of minutes to do something as simple as jam sync your cameras in the field could save hours of time in editing. High-end cameras all have capabilities for that, so there are no excuses.

But even many lesser-capable cameras are still able to work with timecode, and even when they aren’t, there are many workarounds, add-on boxes, and so on. Some of the workarounds are simple and inexpensive ”“clapboards, handclaps, or flashlights ”“ but timecode really does work better, and for multi-cam, that usually means time of day, free run.

I should mention that there are a lot of really cool iPhone slates out there. “Movie Slate” by PureBlend Software even lets you jam-synch multiple slates, and generates EDLs, XMLs and ALEs for Final Cut and Media Composer. You can even e-mail them right out of your phone to your editor.

Time Code Slate

Longitudinal timecode is one way to go for these lower-end cameras that don’t handle timecode on their own. A signal gets sent to cameras’ audio tracks, and then picked up in post and converted to auxiliary time code. A company called Ambient makes theLockit Box, a high-quality timecode and sync generator. They also make the LANC Logger for smaller, lower-end cameras. (It actually works on high-end cameras too.) It plugs into the LANC jack, and generates, reads and converts timecode. It also creates XMLs that you can input into your editing software, and start grouping clips right away.

The technology that was used to write code for these devices was done in cooperation with big brains from around the world, such as Andreas Kiel from Spherico and Bouke Váhl of VideoToolShed.

Ambient has a lot of other cool products for timecode with multicam. Sequence Liner takes timecoded clips, and lines them up in your sequence on vertically stacked tracks. This gives you what we call a sync map of your multicamera show, and then make groups from the sync map. And, Video ToolShed has the AuxTCReader for converting LTC to Aux TC in FCP. (Avid does this natively).

Timeline From U2 360º Tour EPK. Courtesy MHP3.com, Live Nation and U2.com

|

Mitch Jacobson is the owner and executive producer at Category-5 Entertainment, a creative editing boutique in New York City. Mitch is an Apple Certified Pro and specializes in Avid and Final Cut Pro systems. He has over 25 years experience cutting network TV programs and concert films for A&E, CBS, Fox Sports, E! Entertainment, PBS and others. He is also a keynote presenter at the Post | Production World Conference at the National Association of Broadcasters Conference, April 12 -15, 2010 in Las Vegas. |

|

This article was originally published at CreativeCOW.net

Recent Comments