Documentary Editing – Where Is the Truth?

Pare Lorentz, the most influential documentary filmmaker of the Great Depression of the 1930s, defines a documentary film as “a factual film which is dramatic.” There are many different definitions of documentary. Rather than worry about the exact definition, it is more important to see examples of documentary films which illuminate the subject.

Lorentz’s “The Plow That Broke the Plains,” (1936) shows the devastation caused by the Dust Bowl. This 25-minute film certainly fits his definition of documentary, but it also has a point of view. It has been criticized for blaming westward bound settlers for the ecological crisis caused by intense farming practices which led to severe erosion of the topsoil. Some parts of the film were staged. Whether or not it is objective, it did succeed in bringing attention to a serious problem. It is a moving film. You can view

“The Plow That Broke the Plains” here. Or watch it here.

Many documentaries have a point of view. Few are as neutral as the filmmakers might have you believe. There’s nothing inherently dishonest about this unless the film is presented as neutral. In some ways the editing of a documentary is no different from the editing of a feature film at a similar budget. A feature films relies more on a script than a documentary does. Documentaries tell factual stories rather than fictional stories, but the truth is always colored in some way.

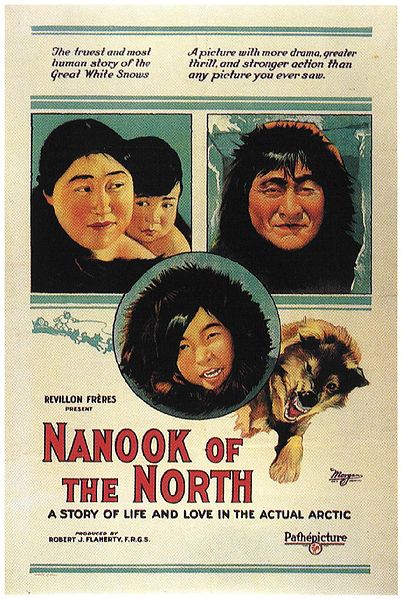

Robert J. Flaherty’s “Nanook of the North” (1922), considered the first feature-length documentary, tells the story of the struggle of an Inuit family living in the Canadian Arctic. While the film does justice to the Inuit people and their customs, some parts of the film were staged and romanticized. To be fair the camera equipment Flaherty used was large and awkward to move. So filming scenes as easily as we can today with lightweight cameras would be impossible. Nonetheless this is a vivid and compelling story of a challenging life style in a frigid climate.

See Nanook of the North” here.

Nanook is narrated with title screens and music which is just as effective as voice narration. Today narration is typical in documentaries. Most rely heavily on the narration to tell the story. One who disagrees with this practice is documentarian Frederick Wiseman who does not believe in narration. Without narration, Wiseman lets his viewers make their own conclusions about the film. One example is Wiseman’s film “Titicut Follies” (1967) which shocked audiences with an expose’ of the brutalities at a Massachusetts hospital for the criminally insane. The film was banned by the state of Massachusetts for many years. It was finally released in 1991. “Titicut Follies” demonstrates that a powerful and moving film does not need narration.

Unlike other documentaries, Wiseman’s films do not progress chronologically. The segments are arranged in themes, more like an essay. Interviews are quite common in most documentaries and television, but Wiseman’s documentaries do not use any interviews.

Wiseman says that his films are not unbiased and, in fact, cannot be unbiased. The very fact that one is making a movie brings a bias or point of view to the process. When one brings a camera, story idea, editing and workers to a film project, a point of view is likely to develop. As Wiseman says [My films are] “based on un-staged, un-manipulated actions… The editing is highly manipulative and the shooting is highly manipulative… What you choose to shoot, the way you shoot it, the way you edit it and the way you structure it… all of those things… represent subjective choices that you have to make.

“All aspects of documentary filmmaking involve choice and are therefore manipulative. But the ethical … aspect of it is that you have to … try to make [a film that] is true to the spirit of your sense of what was going on. … My view is that these films are biased, prejudiced, condensed, compressed but fair. I think what I do is make movies that are not accurate in any objective sense, but accurate in the sense that I think they’re a fair account of the experience I’ve had in making the movie.

“I think I have an obligation, to the people who have consented to be in the film, … to cut it so that it fairly represents what I felt was going on at the time in the original event.”

Wiseman’s films can be seen on PBS. They may also be purchased from his distributor at http://www.zipporah.com. The site also includes a list of video stores where Wiseman’s films can be rented.

Good points about “bias” in film. The viewfinder is a point of view.