By

Doug Graham

The DV Station by Canopus is a turnkey DV editing system, based on a portable PC from Mitac and the Canopus DV Raptor capture and editing card. It comes fully equipped with a good selection of both hardware and software, and is literally ready to edit “right out of the box”.

Hardware Specs:

- Pentium PIII 550 processor

- 128 MB RAM

- 2 GB system drive

- 26 GB UDMA video storage drive (about 2 hours worth of video storage)

- 15″ built-in LCD monitor

- Built-in stereo speakers

- Built-in 10/100 Ethernet connection

- PCMCIA port

- IR communication port

- Parallel, serial, and USB ports

- Logitech keyboard and two-button wheel mouse

Software Bundle:

- Windows 98

- Raptor Edit

- Raptor Navi (auto scene detection and logging tool)

- Raptor Audio (audio capture from DV source material)

- Raptor Video (video capture, batch capture, and seamless (>2GB) capture)

- Adobe Premiere 5.1c

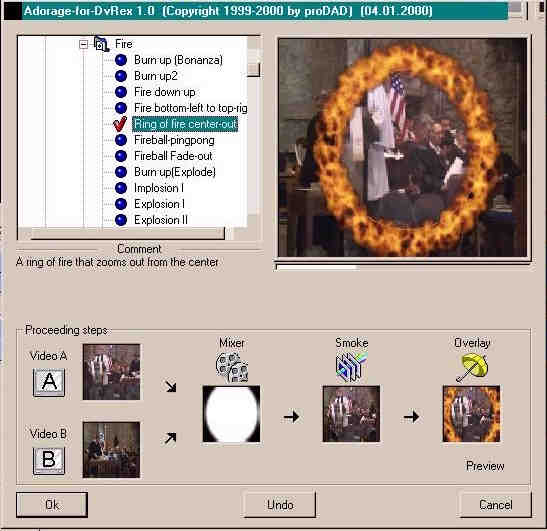

- Adorage (transition and effects program)

- SoftXplode (transitions and effects)

- Crystal Graphics 3D Impact! (3D flying logo animations)

- SmartSound (music creation and editing)

All of this comes in a package that is about the same size as an iMac, and has much the same philosophy — the monitor and the PC unit are integrated into a single desktop unit. Think of this as the PC version of the iMac and iMovie.

I tested the DV Station by editing a typical event video project on it. The project was a high school graduation, and consisted of about six minutes of opening titles, lead-in shots, and interviews with students, followed by a long two-camera shot of the graduation ceremony, and closing with more shots of the students and families after the ceremony. The conclusion is a credit roll consisting of the names of the graduating seniors.

I was amazed at the speed and simplicity of the DV Station, compared to the FAST Video Machine system I normally use. A whole rack of decks, a full tower computer, a 19″ monitor and an NTSC monitor were replaced by a single desktop box and my TRV-900 camcorder. Connections have gotten a lot simpler, too. Instead of a cable for video, two for audio, and another for deck control, everything was done over the IEEE 1394 “Firewire” cable. The Raptor card does take an additional cable to enable real time hardware-supported video preview (it uses your camcorder’s DV codec to provide an excellent quality preview on your computer monitor). However, this feature is not required, and I found the software-only preview to be quite acceptable for editing purposes.

The Raptor Navi utility is the logging tool with automatic scene detection. This proved very useful and quite accurate. Running through a tape at “standard” speed resulted in only two mistakes by the program — it missed one scene transition, and found a transition that wasn’t there. These were quickly edited out by hand and the resulting playlist was imported into Raptor Video for capture.

Raptor Video is the built-in capture tool, but I had to do a little adjusting to make it work. You can manually capture, or batch capture a playlist, or “seamless capture” a long file that exceeds Windows’s 2GB file size limit. However, you can’t combine batch capture and seamless capture in the same operation, so I had to edit my long files out of the playlist and go back to do a seamless capture on them later.

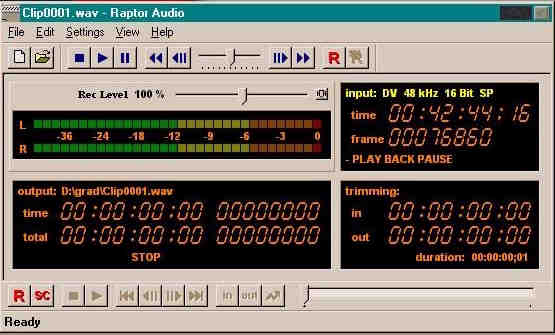

Raptor Audio (for capturing)

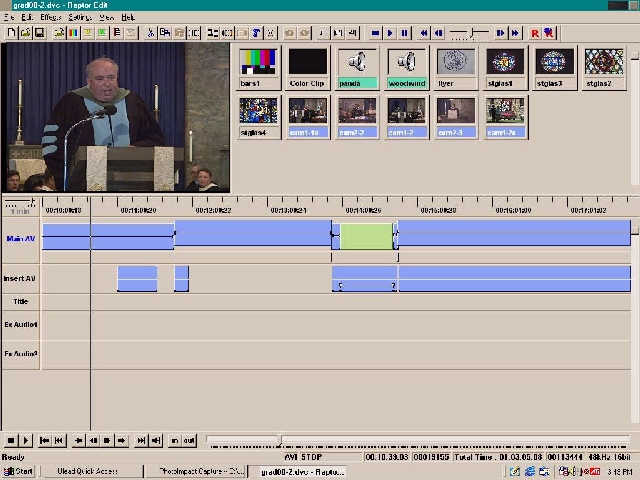

Raptor Edit

Raptor Edit is really the “core” application of the DV Station. It’s a basic editing tool, and I found it to be very fast and intuitive. However, I do feel it has some serious limitations for the professional editor. Most vexing to me was the lack of media management and identification tools. For example, clips in the timeline aren’t labeled with picons, time code values, or filenames. There is a “Film” track that shows picons, but these often do not line up with the actual clips containing the material, and proved pretty useless in identifying a particular clip.

The timeline is also very “sticky”. Once a clip is there, it can’t be dragged off and put back in the project bin. (At least, it didn’t work for me. Other users of the very similar Rex Edit software say they can do this.) However, a clip can be copied to the bin and then deleted from the timeline in two separate operations. Another aspect of the editor’s “sticky” nature is that clips can’t be slid apart, creating a hole to drop something else into. Clips can be “wedged” between existing material, but the lack of labels often made me wonder whether the clip had gone where I intended.

Split edits, where the audio transitions at a time either before or after the video, are not possible without considerable working around. If you needed to make split edits often, you could use Adobe Premiere which is included as part of the package.

Dragging the cursor off the screen to reposition the timeline proved frustrating; once it went off screen, the timeline scrolled far too fast to catch the position you want. A better method is to zoom the scale out, position the cursor where you want to work, then zoom in. Or you can scroll rapidly with a drag bar at the bottom of the window.

The “separate” function, which allows a longer clip to be chopped up into smaller segments, worked instantaneously. However, the new short clips can’t be renamed; they all keep the name of their parent clip. Again, this made it difficult to tell what I was doing as I rearranged material on the timeline. Another way to do this that will allow renaming is to make a “ref .avi” file from the new clip. This takes a bit longer, but doesn’t eat much disk space since the reference file is simply a pointer to one or more actual .avi files.

Companies Mentioned

• 3DImpact! by Crystal Graphics

•

The audio editing tools allow the placement of control nodes and “rubber band” adjustment of clip volume. There are also two additional stereo audio tracks for music and voice over material. There is no audio waveform display, and I didn’t find any way to affect the left and right channels separately.

There’s no provision in Raptor Edit for adding markers to the timeline; I’d like to have this function to make editing to the beat of a music track easier. However, you can work around this to some extent by using temporary nodes on the audio level track as markers.

Transitions and titles were well-integrated into the package, and I was pleasantly surprised at the rendering speed. A one-second dissolve renders in about two or three seconds. I didn’t feel at all slowed down by the lack of real time response in this area. Titles took somewhat longer to render, maybe thirty or forty seconds for a ten second title. However, the lack of real time display was made up for by not having to go to an external CG application to create titles. Titles may have their own transitions and/or motions applied, and are keyframeable. Soft and hard drop shadows of several types, as well as embossing for a “3D” look to the titles are included in the titling tools. Be careful to keep title color values within NTSC legal limits. I found it necessary, for example, to tone down some small print white text even below the 235,235,235 “white” generally considered safe for NTSC video to prevent it from blooming.

I found Raptor Edit to be generally stable, but I did manage to get it to crash a few times. A quick shutdown and restart of the program fixed it every time, with no loss or corruption of the ongoing project. At one point, the system’s video drive was about 98% full. At this point, Raptor Edit seemed to start introducing spurious changes into the project, such as losing audio nodes and rendered transitions. Most users suggest keeping the drives less than 80 – 90% full to avoid problems like these. Even so, the project played from the very full drives with no dropped frames in 59 minutes of video.

I did notice some minor problems apparently caused by the video driver for the LCD display screen. On occasion, icons or parts of windows (for example, the minimize/maximize buttons in the upper right hand corner) would disappear or go black. The controls were still functional, and the image would reappear if the window was minimized and then restored. Hopefully Mitac will release a driver update to fix this annoyance.

I ventured into the SmartSound audio package to create some background music. This is a great tool, and can be made even better by purchase of additional SmartSound music CDs. You don’t have to know a thing about music, or notes, or chords to use this program. The way it works is to string together a number of different short “elements” into a soundtrack of whatever length you specify. You can do this very quickly through the use of the “Maestro” function, which asks you a series of questions to build a basic composition in the style and length you want. You can then rearrange, add, or delete elements (they sound fine in any order you put ’em), and apply effects such as echo or flange to some or all of the composition. When you have everything just the way you want it, you then export the composition as a .wav file, which can be brought into your video project. This was a great deal of fun, and produced background music nearly as good as my favorite buyout libraries (in fact, Music Bakery makes a lot of the music element CDs for SmartSound). If you don’t have SmartSound in your arsenal, you lack an essential tool in your arsenal. Get it!

The Adorage transition package has several hundred editable transitions, and is quite impressive. The transitions include alpha channel effects and distortions like ripples. You can also add smoke and fog. Some of the transitions use 3D models to wipe from one video clip to the next, such as a 747 jet flying across the screen. Fire and explosions are included in the mix, too. If that, plus the included SoftXplode transitions, aren’t enough for you, Boris FX can be added to the package. Oh, and you’ll want to download and install the free Adobe Acrobat reader so you can look at the .pdf help file for Adorage — although you might not need it; it’s a very intuitive package and works right from within Raptor Edit like any other transition.

I can’t speak very highly of the 3D Impact! animation package. It proved no more stable in the DV Station than it had in my old P133. However, it does give you some basic tools for creating 3D titles and flying logos. The image quality is very good, and the metallic textures are among the best available. The version of 3D Impact! included with the DV Station bundle lacks some of the features of the full 3D Impact! Pro version, such as some beveling options, controllable lighting, and the use of images as surface materials. If you’re serious about animation, you’ll want to move on to something more powerful, flexible, and stable, like Animation Master or even LightWave 3D.

Adobe Premiere is getting bundled with everything these days. It’s a lot more powerful than the Raptor Edit application, and many Canopus users do their basic “cuts and dissolves” editing in Raptor Edit and then move the project into Premiere for complex multi-layering work. I found Premiere to be less intuitive than Raptor Edit, and a bit less stable. In addition, work done in Premiere suffers a slight loss of visual quality. This is because Premiere translates from DV’s YUV color space to RGB, and back again. Also, rendering in Premiere is considerably slower than in Raptor Edit. I didn’t attempt to scale Premiere’s learning curve for this project, but stuck pretty much to Raptor Edit. (If you prefer Edit DV or Media Studio Pro, these applications will also work with the DV Raptor, but are not included in the DV Station bundle.)

Most systems require the addition of several extra software applications to be considered a complete “video studio in a box”. The DV Station does well in this respect. The only things I would want to add are apaint program, such as Photoshop or JASC’s Paintshop Pro, and a sound editing program such as Sound Forge or Cool Edit, but that’s about all.

So how about long projects? My sample job was about an hour and 45 minutes in length, with about four hours of source video. The DV Station’s 26 GB video drive holds just over 2 hours of material. In practice, it’s a bit less than that, since you should leave a safety margin as mentioned earlier, plus leave room for audio files and Raptor Edit’s (or Premiere’s) temporary files of rendered material. So for long projects, some planning is required. I split the job into three parts, with still images as the “bridge” between them. At the end of a segment, I would transition to the still image for about 10 seconds. The segment was recorded by playing back the timeline from Raptor Edit into a Sony DHR-1000 VCR. Then the timeline and the disk were cleared and a new project was begun. This next segment was started with the same graphic that ended the previous one. This meant that the DHR-1000 didn’t have to be frame accurate when picking up the next segment. That’s important, because even if your recording deck is accurate, the Raptor Edit software doesn’t recognize or control its positioning in the same way as more expensive systems. Raptor Edit has a “sync record” feature, which always starts playback from the start of the project. The manual states the recorder will also “be rewound to the start of the tape”, but fortunately that isn’t the case. The recorder is backed up a few frames from wherever it is paused, and DV Station attempts to place the start of the timeline at that point on the tape.

All this sounds rather haphazard, but it wasn’t actually that bad in practice. What matters is results, and that’s what I got.

How hard was it, really? Well, I met my client’s deadline, and with no more late nights than I would likely have spent using my more familiar system. That sort of productivity speaks for itself. However, if I was planning more long projects, I would consider a system with more video storage, such as the Raptor-based turnkey tower systems sold by Core Microsystems.

What about image quality? I was extremely pleased with the quality of the native DV editing provided by the DV Station. The final edit master looked identical to the original footage, as advertised. Titles were crisp and clean, and keyed well over video or stills.

In addition, Canopus offers free telephone technical support during normal business hours, and a call back or fax-based support option for off-hours. When I called the Canopus support line (the number is right there on the desktop image!), the call went through in less than five minutes, and the support person on the other end was friendly and knowledgeable. Canopus also offers free software upgrades for their products, available for download at their web site. Both bug fixes and additional functionality have been provided by past upgrades. Unlike some companies that abandon a product after six months or a year, Canopus has developed a reputation for supporting their products, even after newer models have become available.

Don’t expect to do a lot of hardware upgrades with the DV Station, however. Canopus sells this turnkey system as a “sealed box”. If you open it up to upgrade the processor, memory, or hard drive, Canopus specifically states that the warranty won’t cover such modifications. The DV Station makes the most sense for those who want the security of a single, unified, turnkey system.

But if you’d rather buy a system and upgrade it one piece at a time, then buy the bare Raptor board and put it in a PC box. You will get more options and power, but you also get more responsibility.

The Bottom Line

Is the DV Station a good value? I’d say, definitely “yes” in absolute dollar terms. The Mitac portable computer alone would cost almost as much as the suggested list price ($2,995) of the fully loaded DV Station. Kind of like buying a portable computer and getting a video editing system thrown in for free. In terms of usefulness, it’ll depend on your intentions. This is not as portable as a battery operated laptop. But it is certainly more portable than a standard tower computer.

If you want to edit event video as a full time business, you may be better off with a system that offers greater storage for programs and video data, as well as one that has some real time features. Canopus has such systems available (DV Rex RT, or the R3 turnkey system), but they cost quite a bit more than the DV Station.

The person who buys a DV Station will probably be one who wants to get his or her feet wet in video editing without getting into a lot of configuration hassles with a bare card. Or possibly a videographer who has to watch the budget, and is willing to accept some storage and rendering limitations to keep costs down. Another ideal buyer would be a school that wants to put together a classroom of inexpensive editing systems for a media class (the DV Station is especially good for this application with its built-in Ethernet connectivity; a whole slew of them could be connected to a classroom server.) For anyone looking for a low-cost, high quality native DV editing solution, the Canopus DV Station should be on their “short list”.

Doug Graham has been making industrial and event videos for eight years. Doug can be reached on the Video University Forums

Recent Comments